Niger J Paed 2014; 41 (4): 307– 3 11

ORIGINAL

Eke CB

Comparison of actual (measured)

Ubesie AC

Ibe BC

weights and heights with the

standard formula methods of

estimation among children in

Enugu

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v41i4,3

Accepted: 13th April 2014

Abstract

Background: In

paediat-

age. The level of significance was

ric practice, weight and height are

set at p<0.05.

Eke

CB

(

)

required for therapeutic and diag-

Results: A

total of

370 children

Ubesie AC, Ibe BC

nostic interventions. In some cir-

Department of Paediatrics, University

were studied. They were aged one

of

Nigeria Teaching Hospital

cumstances actual anthropometric

year two months to 12years.

Ituku- Ozalla, Enugu

measurements are not possible and

Among children ≤ 2 years the

Email: chriseke2006@yahoo.com

estimates are used. Several formu-

measured weights and estimated

lae are in use for weight and height

values showed no significant dif-

estimations. The adequacy of these

ference. However, in children

estimates has not been tested for

3-5years, the estimated weights

our children. The aim of the cur-

were significantly lower than the

rent study was to compare the ade-

measured weights. There was no

quacy of formula methods of

consistent relationship for children

weight and height estimation with

7–12 years where a different for-

measured

values in children.

mula was used to estimate weight.

Materials and Methods: This

was a

For heights, the estimated values

comparative observational study.

were significantly lower than the

Children who met the inclusion

measured except for two year olds

criteria were selected consecutively

where both where almost similar.

and studied over a two month pe-

Scatter diagrams comparing actual

riod using a semi-structured ques-

and estimated plots showed linear

tionnaire. Weight and height of

relationship.

each child were measured and re-

Conclusion: The

current methods

corded to the nearest 0.1kg and

of

estimation are underestimating

0.1cm respectively using standard

weights and heights of children in

protocols. Weight and height for

our environment. There is need for

age were also estimated using the

a

multi-centre cohort study to test

universally

accepted

formulae.

the various formulae in our

Data were analyzed using SPSS

children.

19.0. Paired

t-

test was used to compare the

Key words: Measured,

Estimated,

means of actual and estimated

Weight, Height, Children.

weights and heights according to

Introduction

height as the case may be. This “gold standard” should

be

obtained in all cases when feasible .

2

In

the management of very ill children, anthropometric

However, in our setting and even in elsewhere, it has

data especially weight and/or height are required for

been shown that in paediatric emergency situations re-

therapeutic interventions. Weight and/or height are im-

quiring resuscitation; this is not often done, as all efforts

portant in calculating drug dosages and/or fluid admini-

are geared to save time and apply adequate therapeutic

stration and selecting correct equipment sizes . In some

1

interventions timely.

circumstances actual measurements of weight or height

In

such situations it is often more time saving to use

may not be feasible and estimates are used.

estimated formula in calculating height or weight.

The most accurate method of determining a child’s

Commonly in our setting the age based formulae for

weight or height is to weigh the child or measure the

weight estimation is usually applied as follows: for

308

children aged 1 -6 years: 2n +8; for children 7-12years:

Measurements were taken twice and the average re-

7n- 5/2; while for height estimation in children aged 2 –

corded

in the spaces provided in the proforma.

12

years, the formulae: 6n + 77 (where n = age in years)

The weights of the enrollees were estimated using the

3

is

applied. The adequacy of these estimates has not

following formulae:

been tested for our children. Hence, the aim of this

For children aged 1-6 years, the formula:

2n +

8

(where n = age in years) was applied.

3

study was to compare the predictive accuracy of actual

(measured) with formula estimates of weight and height

For instance a child aged one year six months, the esti-

in

children.

mated weight using the above formula was determined

thus: 2 (1.5)+ 8 = 11.0kg and so on.

Also children aged seven years to twelve years, the for-

mula: 7n-5, all divided by 2 (where n = age in years)

Materials and methods

was

used.

3

This

was a comparative observational study conducted

For height estimation: the

formula: 6n

+ 77

(where n

=

among children aged one year to 12 years attending the

age in years) as recommended for children aged 2-12

years of age) was applied. The estimated height for chil-

3

children’s outpatient clinics (CHOP) of University of

dren aged one year was taken as 75cm.

3

Nigeria Teaching Hospital, (UNTH) Enugu State South

East Nigeria.

The children’s outpatient clinics of the Department of

Data Analysis

Paediatrics UNTH, Enugu renders primary, secondary as

well as tertiary healthcare services to the teeming popu-

Data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0. Paired t- test was

lation of minors in Enugu State and its environs among

used to compare the means of actual and estimated

other services. It runs general paediatric outpatient clin-

weights and heights according to age. Scatter diagram

ics from Monday through Friday with average daily pa-

was plotted to determine the relationship between actual

tient load of 60-80 children. Data was collected by one

and estimated heights; actual and estimated weight

of

the researchers. Ethical approval was sought from the

based on weight formula for children aged 1-6years and

Ethics and Research Committee of UNTH, Enugu.

7

– 12years. The level of significance was set at p <

0.05.

Data collected included age, date of birth, gender, edu-

cational backgrounds and occupation of the parents/

caregivers from where child’s socio-economic class was

Results

assigned using the method proposed by Oyedeji in

4

Ilesha, Nigeria. The respective age of all the subjects

A

total of 370 children were studied. They were aged

were confirmed through their date of births.

one year two months to twelve years (mean age 6.0 ±

Subjects

were excluded if they had any medical condi-

3.7

years). Two hundred and twenty five (60.8%) were

tion that would substantially affect their weight and/or

males while 145 (39.2%) were females. One

hundred

height – amputation, or dwarfism, congenital heart dis-

and

sixteen (31.4%) and 168 (45.4%) children were

eases, dehydration, volume overload, or oedema, severe

from the middle and lower socio-economic classes re-

joint contracture or neurologic deficits e.g. cerebral

spectively. The socio-demographic characteristics of the

palsy that can affect growth. Children who their caregiv-

children are shown in Table 1.

ers gave informed consent and met the study criteria

were recruited using convenient (consecutive) sampling

Table 1: Socio-demographic

characteristics of

the

method from 1 June to 31 July, 2013.

st

st

subjects

Variables

Frequency (%) (N = 370)

The weight was recorded with a Tanita HD-314 portable

bathroom scale and has a maximum recordable weight

Gender:

of

110kg.At the beginning of each measurement day,

Males

225

(60.8)

accuracy of the weighting scales is checked by using a

Females

145

(39.2)

known standardized weight placed on the scale.

Socio-economic class:

Upper

86

(23.2)

Before, each measurement, the scale is usually turned to

Middle

116

(31.4)

‘zero”

to correct for zero error. The children were meas-

Lower

168

(45.4)

ured wearing only a single layer of light / outdoor cloth-

ing. Weights were measured in kilograms to the nearest

Table 2 shows the measured weight (mean ± SD) and

100grams.

estimated weight (mean ± SD) by age. Here for children

two years and or below, the measured weight and esti-

The standing height was measured (for selected children

mated showed no significant difference. However, in

2years and older) using a stadiometer. With the child

children 3-5years, the estimated weights were signifi-

standing upright, the head was positioned in the Frank-

cantly lower than the measured weights. There was no

furt horizontal plane, and the headboard placed carefully

consistent relationship for children 7 – 12 years where a

but firmly on his head. The child was asked to take a

different formula was used to estimate weight. In chil-

deep breath while the reading was made. The height

5

dren7-8years the estimated weights were significantly

measurements were read off to the nearest 0.1cm.

lower than the actual values while in those aged

309

9

-11years estimated values showed no significant dif-

significant (p<0.001).

ference. Also in the 12year olds the estimated weights

Kruskal Wallis test, did not show significant difference

were significantly lower than the measured values.

between the various socio-

For heights, the values were significantly lower than the

economic classes and either the difference of estimated

measured except for two year olds where both where

weight from actual weight (p=0.229)

almost similar.

or

the difference of estimated height from actual height

A

comparison of the mean actual and estimated weights

(p=0.15). The mean bias was 1.15kg for the weight for

and heights according to age is shown in Tables 2 and 3

age formula (95% CI -0.71 to-1.59) and -5.19 for the

respectively.

height for age formula (95% CI -4.55 to -5.83).

A

negative mean bias is noted in both formulae for

Table 2: A

comparison of

the mean

actual and

estimated

weight and height estimation.

weight by age

There was no statistically significant difference between

Mean weight (kg)

males and females; and the difference of estimated

Age

(years)

Actual (SD)

Estimated (SD)

p-value

weight from actual weight (p=0.625). The difference

between mean measured height among females (120.2 ±

1.

10.3±1.3

10.0±0.0

0.340

25.6 cm) and males (114.6 ± 25.8 cm ) was statistically

2.

12.3±1.6

12.0±0.0

0.260

significant (p=0.04).

3.

15±1.8

14.0±0.0

0.001

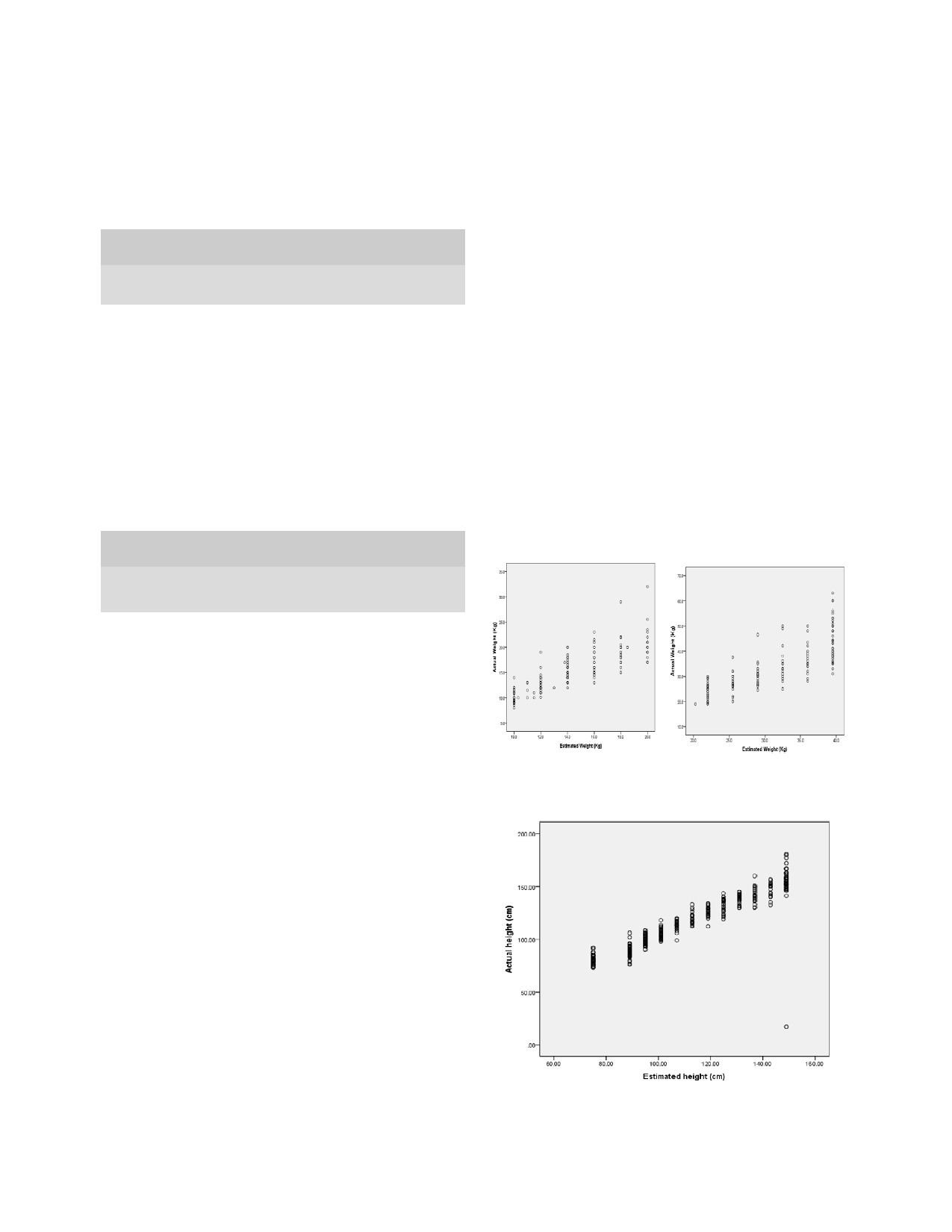

Scatter diagrams comparing actual and estimated

4.

17.2±2.4

16.0±0.0

0.005

5.

19.2±2.7

18.0±0.0

0.030

weights and heights are shown in Figures 1

6.

21.2±3.2

20.0±0.0

0.120

and 2 respectively. The plots showed linear relationship

7.

23.7±3.4

22.0±0.0

0.010

between actual and estimated values. However, there

8.

27.4±3.5

25.5±0.0

0.009

appears to be more positive linear relationship for

9.

30.5±4.6

29.0±0.0

0.140

weights among children

10.

34.0±6.3

32.5±0.0

0.270

aged 7-12 years than those aged 1- 6 years (Fig 1).

11.

37.0±5.9

36.0±0.0

0.480

12.

44.0±7.9

39.5±0.0

0.001

Fig 1: Scatter

diagrams showing

the relationship

between ac-

tual and estimated weights for children aged 1-6 years (left)

Table 3: A

comparison of

the mean

actual and

estimated

and

7-12 years (right).

heights by age

Mean heights (kg)

Age

(years)

Actual (SD)

Estimated (SD)

p-value

1.

80.4±4.6

75.0±0.0

<0.001

2.

88.3±5.2

89.0±0.0

<0.340

3.

99.2±4.8

95.0±0.0

<0.001

4.

105.4±4.3

101.0±0.0

<0.001

5.

112.9±4.6

107.0±0.0

<0.001

6.

120.9±5.6

113.0±0.0

<0.001

7.

125.8±5.3

119.0±0.0

<0.001

8.

132.4±6.6

125.0±0.0

<0.001

9.

138.5±4.6

131.0±0.0

<0.001

10.

141.9±7.4

137.0±0.0

0.007

Fig 2: A

scatter diagram

showing the

relationship between

11.

147.3±7.0

143.0±0.0

0.020

actual and estimated heights.

12.

153.8±22.8

149.0±0.0

0.017

The overall median measured and estimated weights

were 20kg (range 8-63kg) and 18kg (range 10-43kg) and

the difference was statistically significant (p = <0.01)

while median measured and estimated heights were

114.8cm (range 73-177cm) and 107cm (75-149cm) re-

spectively and the difference was statistically signifi-

cant (p = <0.01).

Pearson’s product moment correlation showed a very

strong correlation between actual and formula estimated

weight with an r – value of 0.934 (p = < 0.01) and height

with an r – value of 0.930 (p = <0.01) respectively.

The overall mean measured and estimated weights were

23.2 ± 11.5kg and 21.7 ± 9.8kg respectively. There was

a

statistically significant difference between the mean

actual and estimated weights (p<0.001). The overall

mean measured and estimated heights were 118.8 ± 25.9

cm

and 112. 1 ± 23.1cmrespectively. The difference in

mean of actual and estimated heights was statistically

310

Discussion

were

proposed many years ago. The growth pattern of

children may have changed with better nutrition. Weight

Knowledge of weight and/or height is an invaluable tool

and

height increments occur earlier. This is very obvious

in

paediatric practice. The assumption is that the formu-

in

height as observed in the current study.

Martorell et al

15

lae for weight and height estimation will give a value

documented that obesity levels in-

not significantly different from actual weight and height.

creased overtime but at varying rates, and concluded that

This study shows that both methods of weight estima-

rising incomes in developing countries and increased

tion gave values that were significantly lower than the

‘westernization’

will most likely lead to increased levels

actual values with some outliers in certain cases. Simi-

of

obesity in developing nations. The overall implication

larly, the estimated heights were significantly lower than

is

that they accumulate a lot of weight and excess fat

the measured except for the two year olds where they

mass deposits.

were comparable.

It

has been shown in a previous study that certain weight

In

the paediatric emergency situations, fast and accurate

formula like the new Advanced Paediatric Life Support

methods of weight and height estimation are needed for

(APLS) formula published in 2011 under – estimated

immediate therapeutic interventions in order to save

weight with the under – estimation increasing in chil-

lives.

Many estimation methods currently exist but most

dren aged one to five years . Similarly other methods of

6

may now be overtaken by time as many developing

weight estimation including the Broselow tape and the

countries including Nigeria are grappling with “double

age formulae have also been shown to under- estimate

burden” of malnutrition with obesity/overweight being

weights in studies done in Switzerland and Australia

on

the increase resulting in the fact that the formula esti-

respectively .

1,7

mation of weight or height may be under- estimating the

actual value in many of the children.

It

has being reported that visual , parental estimation

8

9

and

estimation by attending nurses and doctors

11

are

often inaccurate and potentially unreliable.

Previous investigations of the accuracy of parental esti-

Conclusion

mation of children’s weight produced conflicting results;

in

one series estimates were within 10% of the subjects’

In

conclusion the formula methods of estimating

actual weight ; where as in another study only 42% of

9

weights and heights for the various ages in children are

weight were accurate .

10

under- estimating their actual values. This is more obvi-

Similarly, “guessitimation” of children’s weight gives

ous

for height.

inaccurate results .

2

We

have been using these formulae in our local practice

The

under-estimation of weight and height using current

without finding out the actual statistical relationship.

formula methods will result in significant under - dosing

The current trend as found in this study calls for further

of

some emergency drugs, as has been reported in a

studies preferably multi-centred with larger cohort of

similar study by Luscombe and colleagues .

11

children to test the various formulae.

Some of the drugs used in emergencies like phenytoin

Authors’ contributions

employed in treatment of status epilepticns and opioids

used for analgesia should be based on total body weight

Ibe BC: Conceptualization of the study/ critical editing

in

obese patients because of distribution in fat mass .

12

of

the final draft

Considering the fact that under-nutrition is prevalent in

Eke CB: Data collection/ data analysis and study write-

Nigeria especially among under -five children

13,14

it

up

would have been expected that the formula methods

Ubesie AC: Data analysis, and manuscript writing

would over- estimate the weight and heights of our chil-

Conflict of interest: None

dren. These formulae as applied in the current study

Funding: None

References

1.

Black E, Barnett P, Wolfe R,

4.

Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, Behr-

7.

Seddon C, Lockitt L, Dhanjal S,

Young S. Are methods to estimate

man

RE, Stanton BF (editors).

Eseahut M, ISRN Pediatrics, 2012.

weights in children accurate?

Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia,

Article ID: 869634, 4 pages. Avail-

Emerg Med (Fremantle) 2002; 14

USA; 2007; 70-74.

able @: http://

(2): 160 – 165.

5.

Oyedeji GA. Socio- economic and

dx.doi.org/10.5402/2012/869634.

Accessed: November 8 , 2013.

th

2.

Argall JAW, Wright N, Mackway

cultural background of hospital-

–

Jones K, Jackson R. A compari-

ized

children in Ilesha. Niger

J

8.

Hofer CK, Ganter M, Tucci M, et

son

of two commonly used meth-

Paediatr 1987;12: 111-117.

al.

How reliable is length - based

ods

of weight estimation. Arch

Dis

6.

SOWC 2008 statistical tables. The

determination of body weight and

child 2003; 88: 789 – 790.

State of the World’s Children

tracheal tube size in the paediatric

3.

Keane V. Assessment of growth.

2008. Available @:

age

group? The Broselew tape

In:

Nelson textbook of pediatrics,

www.unicef.org/sowc08/docs/

reconsidered. Brit

J Anaesth

18

edition.

th

sowc08.pdf.pp118- 120. Accessed

2002;88:283- 285.

15

January, 2009.

th

311

9.

Anglemyer BL, Hernandez C,

12.

Luscombe M, Owens B. Weight

15.

Ndukwu CI, Egbuonu I,

Brice JH, Zou B. The accuracy of

estimation in resuscilution: is the

Ulasi TO, Ebenebe JC. Determi-

visual estimation of body weight in

current formula still valid.

Arch

nants of undernutrition among

the

emergency department. Am

J

Dis child 2007; 92 (5); 412 – 415

.

primary school children residing in

Emerg Med 2004; 22 (7): 526 –

13.

Cheymol G. Effects of obesity on

slum areas of a Nigerian City.

529.

pharmacokinetics: implications of

Niger J Clin Pract 2013; 16:178-

10. Leffler

S, Hayes

M. Analysis

of

drug therapy. Clinical pharmacoki-

183.

potential estimates of children’s

netics 2000; 39 (2): 215 – 231.

16.

Martorell R, Khan LK, Hughes

weights in the ED. Ann

Emerg

14.

Sebanjo IO, Olayiwola IO,

ML,

Grummer – Strawn LM. Obe-

Med

1997; 30 (2); 167 – 170.

Afolabi WA, Sebanjo OC. Mater-

sity in women from developing

11.

Harris N, Patterson J, Norse J.

nal

and child undernutrition in

countries. Eur

J. Clin

Nutr 2000;

Doctors, nurses and parents are

rural and urban communities of

54: 247 – 252.

equally poor at estimating paediat-

Lagos State, Nigeria: the relation-

ric

weights. Pediatric

Emerg Care

ship and risk factors. BMC Re-

1999; 15 (1): 17-18.

search Notes 2013, 6:286.